A View from the Cellar

A Crash Course in Cellarmanship: Part II

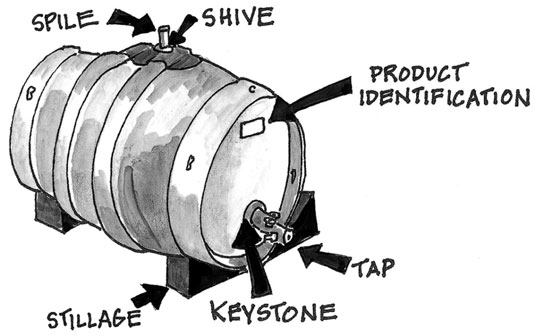

In what I plan to be an ongoing series, I hope to further broader knowledge about real ale, it’s history, practice and relevance. Part one was about the history and anatomy of casks. Part two is about using casks. When filling a cask, first put in the keystone, this is the smaller plug that will be pierced with the tap, then lie the sterilized cask on its side and fill through the side aperture: you may need to use props to hold the cask still or clamp it between your legs. Next, consider the condition of the beer. To avoid over-carbonation, the beer should be fermented to a reasonably-stable final gravity. Make sure there’s a little yeast still in suspension, it doesn’t need a lot, just make sure that it’s not been filtered, if absolutely necessary add a little fresh yeast. Leave at least a litre of head space at the top so that the CO2 has somewhere to gather. Don’t worry about oxygen/air – the yeast will use that up. Add a small amount of sugar, a quarter cup is plenty in a pin, a third for a firkin – dextrose works well as it dissolves quickly, is easily fermentable and has no taste. More-complex, unrefined sugars may take longer to ferment; simple white sugar works well too. If the beer has a high finishing gravity (a sweet finish) then you may want to skip the sugar and leave it a little longer. The traditional way of skipping priming sugars is to stop fermentation when a gravity point or so from the end and allow it to finish in the cask. However, this is best left to professionals with many years of experience.

Often I use syrups like invert sugar for priming, or if you’re feeling daring you could use a fruit syrup – just be careful as too much sugar means you could have an over-carbonated cask which runs the risk of “exploding” where the pressure builds up and pushes out the shive causing gallons of precious beer to spray all over your walls, floor and ceiling. This has happened many times to me. The best way to check if a cask is close to popping is, each day that the cask is left to condition, look at the keystone, plastic ones will usually be concave but as the pressure builds up to dangerous levels the shive will switch to convex – when this happens carefully move the cask somewhere cool and easily rinsable. It should be fine once cooled and moved but be careful when venting! Venting with hard spile, if needed, needs to be done with the cask absolutely horizontal so that the gas space is immediately below the shive in order to avoid a beer shower.

The optional addition of finings should be made here. Finings coagulate yeast and other proteins and drop them out to the bottom of the cask leaving delicious bright beer. I use cryofine which is an isinglass derivative but a little gelatine works well too. There are some effective vegan options here too which work well, perhaps too well in that we need the yeast to do its thing before the finings drop it out. Finings are very effective and you don’t need very much at all, for example Cryofine when mixed only needs 1g/hec – that is one 1gram per 100L of beer! Finings generally keep working and so even a small amount over a long time will clarify the same as a lot for a short time.

Other additions at this point include dry hopping. Leaf hops should be put in a hop bag/sock – I tend to use multiple smaller bags for this as once the hops hydrate and expand they become difficult to take out when cleaning the cask. Be careful adding fruit or herbs at this point as they can referment quickly and cause (yep you guessed it) explosions. Cleaning fruit as well as beer off the walls is even more irritating.

If you want to try this, add them to a secondary fermenter like a carboy, and wait for it to calm down before casking/racking – maybe skip priming sugar too.

When the cask is sealed up by hammering the sterilized shive, roll it around a little bit then leave it somewhere warm (room temp is perfect) for a few days, or a few weeks even a few months! Periodically you can turn it upside down then back the next day back again but you don’t have to – just remember to check the plastic keystone for bulging frequently. As the cask warms up the yeast wakes up, metabolises the extra sugar creating CO2 which dissolves into the beer naturally, hardly any more alcohol is produced. The yeast will continue to secondarily ferment but slowly, the finings will eventually drop most of it out. Store the cask on end with the keystone face up. If using a wooden keystone or shive pay attention to any mould growing on it – this can be wiped off and sprayed with anti-fungal cleaner.

Next time I’ll be talking about stillage, venting and tapping.

This Post Has 0 Comments